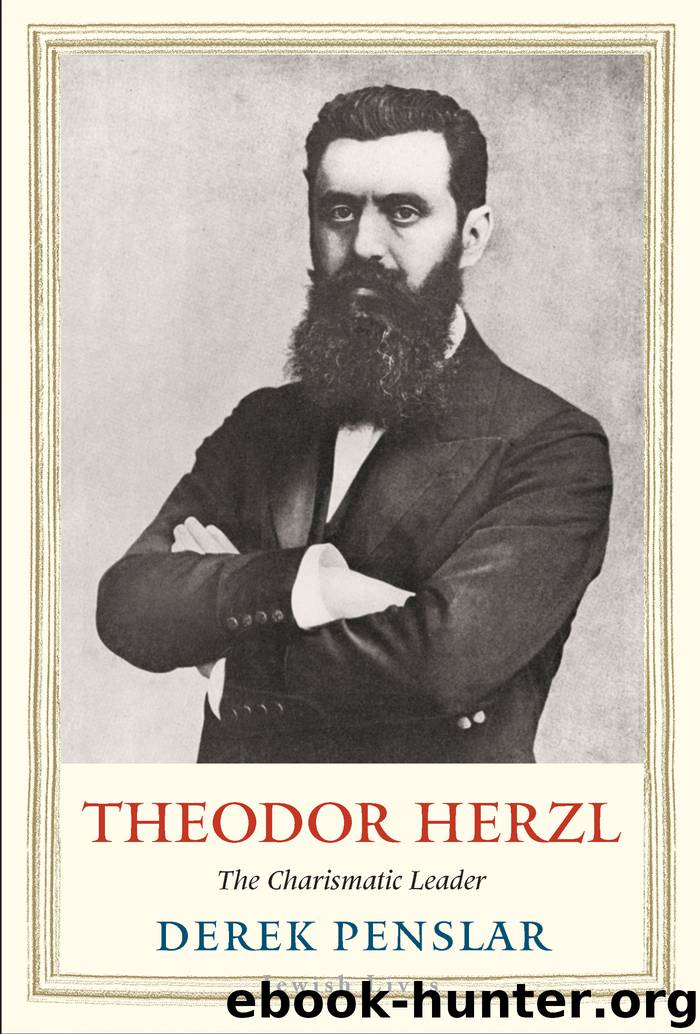

Theodor Herzl by Derek Penslar

Author:Derek Penslar

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2020-02-17T16:00:00+00:00

4

Reaching for the Stars

BETWEEN 1898 AND 1901, Herzl’s Zionist career was at its zenith. The Zionist Congresses, which continued to meet regularly, were only the tip of the iceberg. The Zionist Organization’s central office in Vienna, and the main offices of the Zionist federations of Germany and the United Kingdom, were beehives of activity. Herzl oversaw the foundation of a Zionist bank, a fund for the purchase of land in Palestine, and a flurry of initiatives to win support for Zionism in Europe and North America. Most importantly, these were the years when Herzl finally gained access to the German and Ottoman emperors. In scenes more colorful and dramatic than any of his plays or stories, Herzl met Kaiser Wilhelm II in Palestine at an encampment just beyond Jerusalem’s city walls and Sultan Abdul Hamid II in the splendor of Constantinople’s Yildiz Palace. Herzl was convinced that victory was within reach, and that Palestine would become a German protectorate or an Ottoman vassal state.

Herzl’s social circle was now entirely circumscribed by the Zionist movement. He and Nordau continued to be intellectual soulmates. There remained nonetheless a certain formality in their relationship, as evinced by the fact that despite the close bonds between them, in their correspondence they always used the Sie form to address one another, rather than the more casual Du. Herzl did, however, develop a more intimate rapport with two other men. In 1903, after years of acquaintance, Herzl began to use Du when writing to Alexander Marmorek, a physician and bacteriologist whom Herzl had met in Vienna through the student group Kadimah, and who served on the ZO’s Greater Actions Committee. Herzl admired Marmorek deeply for his commitment to finding a cure for tuberculosis and wrote that he “loved him very much.”1 Herzl’s closest colleague, however, or at least the man upon whom he relied most heavily, was David Wolffsohn. In 1898 Herzl began to call him by the nickname “Daade,” and two years later the two men adopted the Du in their voluminous correspondence. Wolffsohn was an easygoing, affable man, and he and his wife, Fanny, got along well enough with Julie that the Herzls and Wolffsohns dined out together on occasion.

Whereas Herzl treated Nordau with deep respect, his tone with Wolffsohn veered between condescending familiarity and anger born of frustration and disappointment. He praised Wolffsohn for his devotion, but Herzl could quickly become peremptory, accusing Wolffsohn of incompetence, faint-heartedness, and disloyalty. Herzl frequently wrote that Wolffsohn should never forget that he was the deputy and Herzl was the leader, as only he possessed the courage and stamina to handle the extraordinary pressures placed upon him. Herzl testily wrote to Wolffsohn that unlike so many of his indecisive, risk-averse Zionist colleagues, “I don’t shit in my trousers!”2

Herzl’s sense that he was duty-bound to fulfill extraordinary obligations extended to his family. Herzl frequently wrote to friends, and in his diary, that he would quit the Neue Freie Presse were it not for his duty to support his wife and children.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(25804)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(22196)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16321)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(11938)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(6116)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(4807)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(4435)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4136)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4122)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4047)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(3660)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(3585)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(3462)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(3327)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(3285)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(3276)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3099)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3034)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(2933)